Culture

The Sublime, Stupid World of ‘Oh, Mary!,’ Cole Escola’s Surprise Broadway Hit

Published

3 months agoon

By

Press Room

A collage showing Cole Escola as Mary Todd Lincoln, historical photos of Mary Todd Lincoln, and other ephemera.

“Oh, Mary!” is the surprise hit of the current Broadway season: an outlandish comedy with an insistently ahistorical premise, depicting Mary Todd Lincoln as a self-involved alcoholic who dreams of becoming a cabaret star.

Cole Escola in a clip from “Pee Pee Manor.”

The show is the brainchild of Cole Escola, an alt-cabaret performer who, through years of gender-bending sketches on YouTube and onstage, honed the parodic sensibility that informs “Oh, Mary!”

An old photograph of of Mary Todd Lincoln.

The show’s central element is, of course, Mary herself — a warped version of the onetime first lady. Escola, who wrote the show and stars as Mary, created a character who is somehow both serious and ridiculous.

Escola as Mary, wearing a black gown and curls.

So how did the show’s creative team decide what “Oh, Mary!” should look like? Escola had some ideas.

A sketch of the black dress costume.

Escola envisioned Mary’s main gown as heavy and black, her curls bouncy and absurd. “I wanted everything to move and to be fun to play with, but I also wanted it to look like she’s trapped,” Escola said.

The black moire dress, inspired by portraits of, and museum exhibitions about, Mary Todd Lincoln, is bell-shaped, with large puffy sleeves and a pointed bodice; the buttons are exaggerated and the trim is outsized. It “alludes to her inner story of having been a cabaret legend,” said Holly Pierson, the costume designer.

Escola on the stage floor in the black gown.

As the show developed, the dress was shortened, because the more historically accurate floor-length version was causing Escola to trip. “The shortness was necessary for Cole to run around and jump on the desk and do all the stuff on the floor,” Pierson said.

Escola’s bloomers alongside the similar bloomers worn by the queen in the “Alice in Wonderland” cartoon.

The undergarments, which include black tights, white bloomers painted with red hearts, and a ruffled hoop skirt, had to be redesigned several times to make them about five pounds lighter, because the original version was so heavy it impeded Escola’s choreographed movement.

Mary’s hair, a dark brown long bob adorned with curls, is the creation of Leah Loukas, a veteran wig designer. Loukas said the severity of the wig, and its center part, is based on historical images.

A still from “Gone With the Wind” of Aunt Pittypat with her many curls.

The curls, which bounce as Escola flounces, are inspired by characters including Aunt Pittypat in “Gone With the Wind” …

A still from “Cinderella.”

… an evil stepsister in “Cinderella,” and a poetry book Loukas had from her own childhood.

A black and white drawing of a girl with curly hair, alongside a gif of Escola flipping their curls.

The number of curls increased as the show transferred to Broadway from downtown and the creative team decided to play up the absurdity, but striking the right balance — the quantity and bounce of the curls that would move but not obscure Escola’s face — required time and testing.

“It took us months to find the magical sweet spot of comedy and functionality,” Loukas said.

A collage of Escola as Mary, surrounded by old Hollywood actresses.

Escola is a huge fan of old movies and the actresses who starred in them.

… Margaret Sullavan …

… Barbara Stanwyck, and more.

A clip from “The Heiress.”

Especially influential is “The Heiress,” a 1949 film adapted from Henry James’s “Washington Square,” with an Oscar-winning turn by Olivia de Havilland.

“It’s thematically similar,” Escola said: “A woman who doesn’t fit the role she’s supposed to play, and who may or may not be conspired against by the people who are supposed to love her the most.”

A collage of Escola as Mary, surrounded by old Hollywood actresses.

“They’re all ingredients in me, and I’m an ingredient in Mary, so there’s just Old Hollywood microplastics throughout the DNA of my Mary Todd Lincoln,” Escola said.

A collage of Escola being held by another character in the play, surrounded by similar embraces from old movies and the cover of a romance novel.

The sets and the staging are informed by a nostalgia for classic cinematic imagery. “Old American tropes are a signature piece of Cole’s work,” said Andrew Moerdyk, one of the scenic designers.

For example, the brief clutch between Mary and her acting teacher looks like the cover of a romance novel, or a scene from a romantic movie.

A clip from “Gone With the Wind.”

“I’m of course inspired by romance in old movies, whether it’s Scarlett and Rhett or Heathcliff and Cathy,” Escola said, referring to the romantic couplings at the heart of “Gone With the Wind” and “Wuthering Heights.”

A design mock-up of the saloon set alongside a photo of the real set.

A bar where the Lincolns go to drink looks like a saloon from an old western, with its dark wood and swinging door. Nobody worried about what a bar near the White House actually might have looked like in the 1860s.

An old photo of people drinking in a saloon.

“We looked at Victorian saloons of the period from all over America, and they had this beautiful heavy woodwork, and usually had a mirror,” Moerdyk added. “We wanted to distill it down to the essence of what a saloon was.”

Silly props from the saloon set.

The set was created by the design collective dots. Moerdyk described the tone as “rigorously stupid.” “Usually we go to great lengths to mask the tops of walls and erase anything phony, but here we leaned into the theateriness of it all,” he said.

A design mockup of the White House office set for the play, alongside the real set.

The show’s set is meant to be reminiscent of community theater — more stagey than naturalistic, so that when you look at it, you know you’re seeing actors in a play.

The White House office, for example, has two doors on the same side of the room to facilitate actor entrances and exits; the walls are angled to make it easier for audiences on the side of the theater to see.

Zooming in on the two sets of doors.

“That office makes zero sense architecturally — it just looks like a set, and that was intentional,” Sam Pinkleton, the show’s director, said. “Everything is cheated so that the audience can see it.”

“The directive was, ‘You are not designing a play. You are playing designers designing a play,’” Escola said.

“It’s sort of the straight man to the comedy of the writing. The walls move every time we slam a door, but it’s not a ‘Ha ha, look at this set,’ it’s more ‘Look at how seriously we were taking this play with our limited resources.’ It’s literally the backdrop for the comedy.”

“The books on the shelves are painted spines that are totally flat, and you can see from the side that there are no books there,” Moerdyk said.

“We would never do that usually, but it was really fun to be allowed to be stupid.”

A collage of the saloon bar with the R U M bottles.

Another example: “The labeling is the most basic version of what a prop would be,” Moerdyk said. “Downtown we didn’t spend any time thinking about what the liquors would be — we just wrote the word ‘Rum’ and ‘Whiskey’ on bottles and stacked them.

“And when we moved to Broadway, we needed to make that idea register to the back of the house, so we ended up labeling them ‘R’ and ‘U’ and ‘M.’ We had a lot of fun thinking about, ‘What is the dumbest version of this idea, and how can we make it be funny?’”

As the show developed, the creative team leaned into the set’s humor. “When we started there were some things that felt too underplayed or muted or naturalistic, like, ‘Oopsie, we’re doing Chekhov,’” Pinkleton said. Instead, he said, the show works best when “everything is taken a step too far.”

A collage of Escola as Mary, with the Lincoln character, surrounded by reference images of the Lincoln assassination.

The show’s aesthetics get more precise as the story progresses.

An old drawing of the assassination.

For the assassination scene at Ford’s Theater, the designers opted for a greater degree of verisimilitude, imagining that some in the audience would have fairly specific expectations for what that would look like from photographs and paintings depicting the scene.

“We wanted it to be the punchiest, most recognizable, easy-to-clock symbol of Ford’s Theater,” Moerdyk said.

A design mockup of the theater booth set alongside the real set.

“We tried versions that were high concept, but then Sam said, ‘What if we just put the booth in the middle of the stage, surrounded by darkness,’ and the image of that booth in the dark void is so successful.”

A collage of Escola as Mary, wearing a blue dress, surrounded by a costume sketch, swatches, and an old drawing.

The blue dress that Mary Todd Lincoln wears in the assassination scene is a good example of how the show’s designers put their own spin on history, informed by midcentury film aesthetics.

Mary Todd Lincoln did have a blue velvet dress, but it’s not what she wore that fateful night, and it wasn’t as vibrant as the outfit in the show.

“Ours is a little more bright and in your face,” said Pierson, the costume designer. “We wanted it to be this empowerment dress — brash and almost tacky.”

The full moodboard collage.

The show’s design winds up as both a homage and a spoof, made by people who love theater and also laugh about it.

Pinkleton, the director, summed up the approach, saying, “We wanted the whole thing to be a warm embrace of doing a play.”

Cole Escola is scheduled to star in “Oh, Mary!” until Jan. 19, and then Betty Gilpin will step into the title role for eight weeks. Tickets for the show are on sale through June 28; the production has not said who will play Mary Todd Lincoln following Gilpin.

You may like

-

‘Oedipus’ and ‘Rocky Horror Show’ Are Returning to Broadway

-

‘Hamilton’ Cancels Kennedy Center Run Over Trump’s Takeover

-

‘Mamma Mia!’ Is Returning to Broadway This Summer

-

Sadie Sink Heads Back to School, in Broadway’s ‘John Proctor Is the Villain’

-

How Patina Miller, of Starz’s ‘Power’ Series, Spends Her Sundays

-

15 Queer Historical Romance Books to Dive Into the Genre

Walton Goggins Says He Had Penis Stunt Double on Righteous Gemstones

Jax Taylor Cocaine Addiction: Vanderpump Rules Cast Speaks Out

Love Is Blind Cast Reacts to Strange Reunion Looks: See the Outfits

G$ Lil Ronnie Murder Suspect Arrested

A Fashion Photographer Conjures the Ghosts of Georgia’s Past

Benny Blanco Hilariously Does Selena Gomez’s Makeup: ‘I Did Well’

Ashley Iaconetti Shares What She Made Each Day on Bachelor in Paradise

This $43 Resort-Chic Coverup Is Trending on Amazon

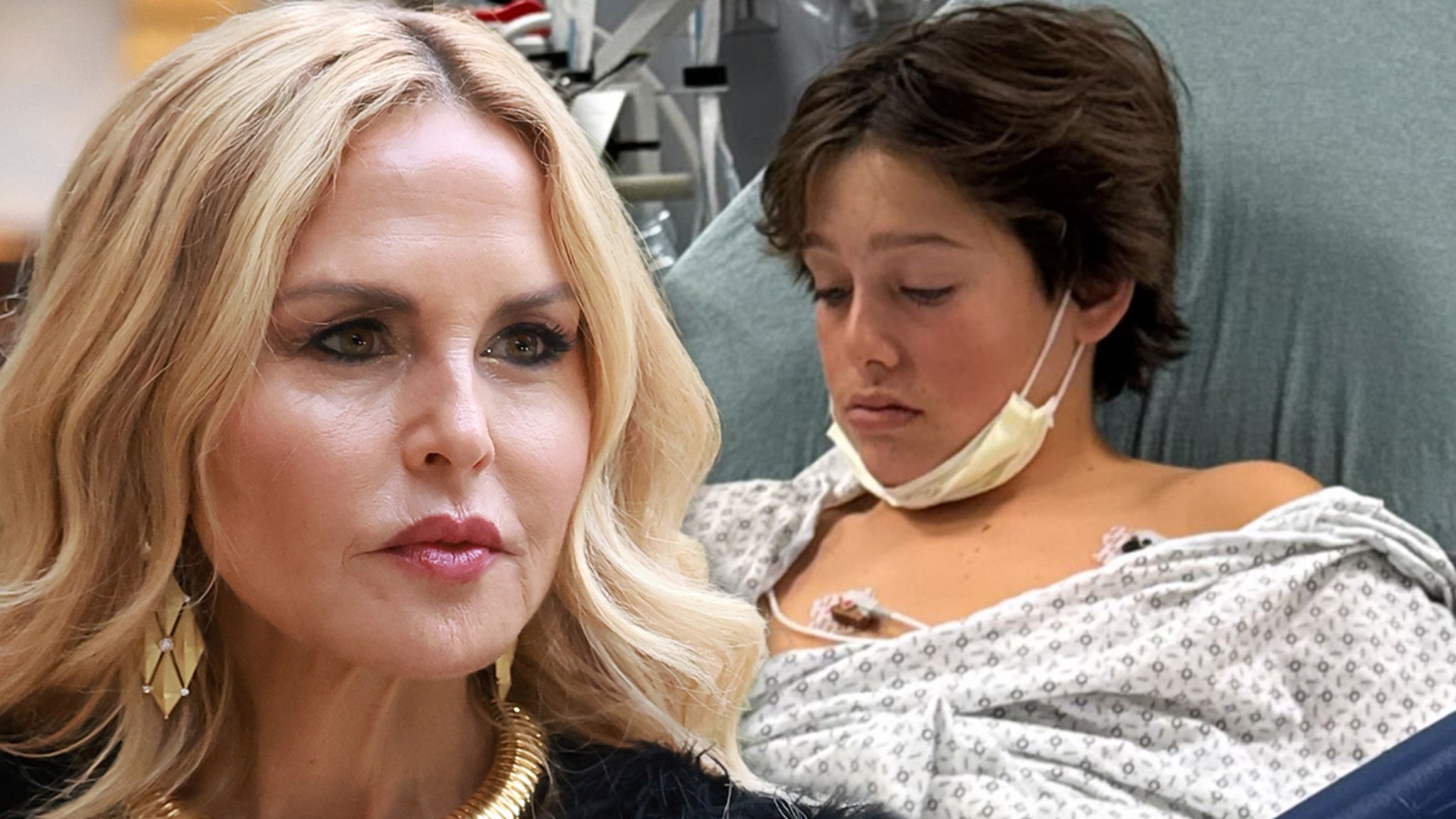

Fashion Designer Rachel Zoe Says Son Was Hospitalized After E-Bike Crash

Gene Hackman’s Gritty, Grouchy, Old-School Style

Madison LeCroy’s Top Amazon Picks for Pregnancy and Baby Girl

Meghan Markle Channels Lifestyle Mavens in ‘With Love, Meghan’ on Netflix

Conan O’Brien Jokes He’ll Be ‘Shirtless and Oiled’ During 2025 Oscars

David Johansen: 15 Essential Songs

Haider Ackermann Leads Tom Ford Into a New Era

Texas May Rename the New York Strip

Love Is Blind Cast Reacts to Strange Reunion Looks: See the Outfits

This $43 Resort-Chic Coverup Is Trending on Amazon

Kate Hudson’s Perfect Beige Blazer Look is Just $50 on Amazon

Kieran Culkin Asked for More Kids at the Oscars. When Is an In-Joke Worth the Risk?

A Cheeto Shaped Like the Pokemon Charizard Sells for Nearly $90,000

Kanye West’s Ex Amber Rose Thinks He ‘For Sure’ Dresses Wife Bianca

Shop This Seamless Underwear Set at $2 a Piece