Culture

Judith Bernstein at 82 Comes Back Swinging

Judith Bernstein and her work share a striking trait: a potent brew of provocative humor edged with anger. An indelible cackle with a crackle, as powerfully expressed in vividly hued paintings strewed with tart, topical text.

“I never toned down anything,” Bernstein said in an obvious understatement. The artist found early inspiration in the graffiti she saw scrawled in the men’s room at Yale, where she was a graduate student in the 1960s. She quickly understood that scatology could be used in the service of satire, making it her trademark trope and putting her own spin on political caricature.

She made her mark in the early 1970s with large-scale charcoal-drawn screws — hairy phalluses as lethal projectiles — that were offshoots of the smaller penile images she incorporated into the anti-Vietnam War drawings and paintings she did at Yale.

But after her first few shows at A.I.R., the feminist gallery she founded with fellow artists Susan Williams, Nancy Spero, Agnes Denes and Howardena Pindell, among others, Bernstein found herself alienated from not only the male art world, but also from her feminist cohorts, who objected to the use of male genital imagery, even to fight the patriarchy.

When her work “Horizontal” (1973), an image of a huge screw, was censored from a 1974 show of women’s art at the Philadelphia Civic Center Museum — the Metropolitan Museum of Art acquired it in 2023 — she was rarely exhibited for 30 years or so. She resurfaced at the New Museum in 2012 in a show aptly titled “Judith Bernstein: HARD,” with her signature boldly painted on the lobby windows.

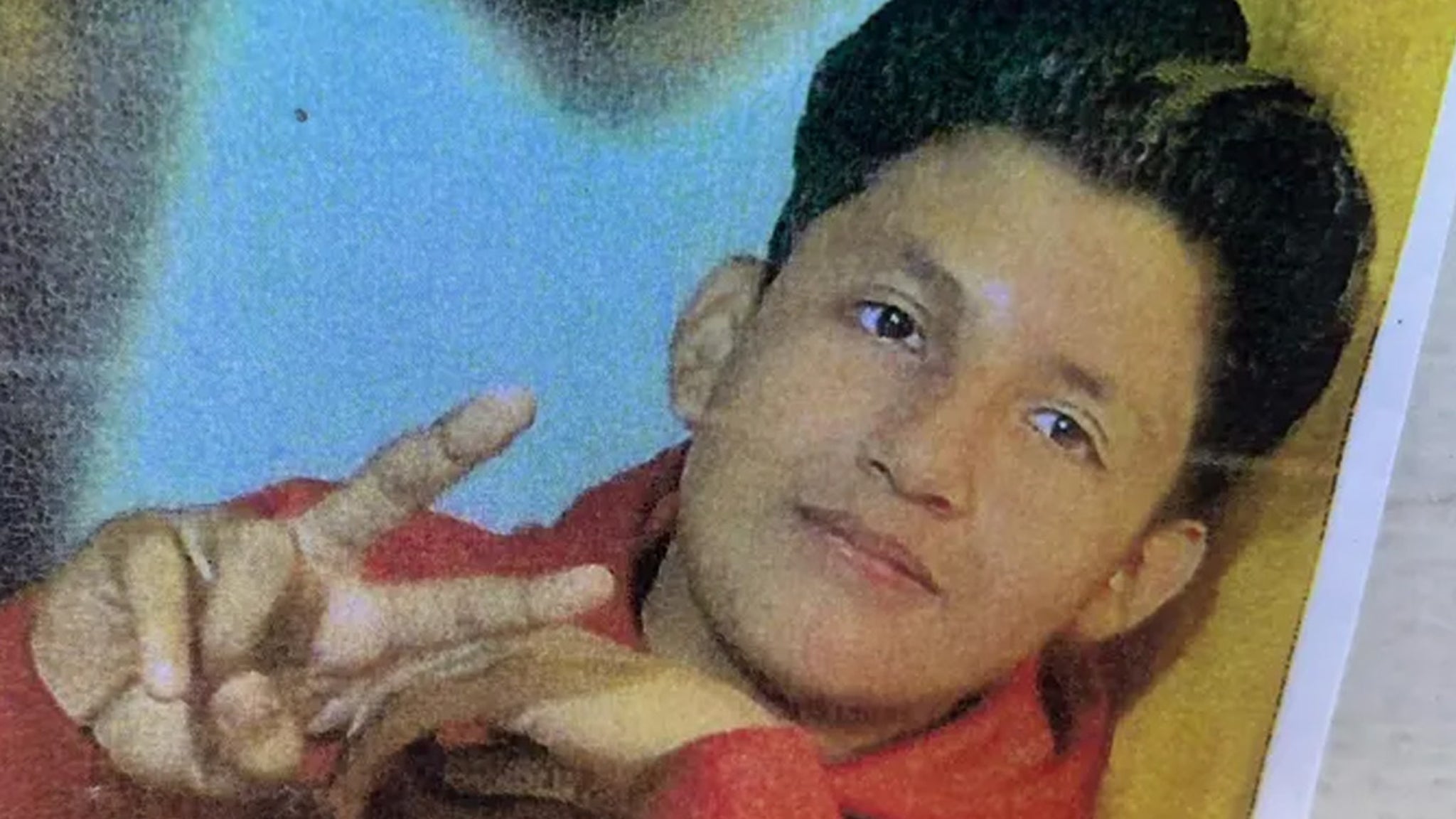

On Jan. 9, the opening night of her new show, “Public Fears,” a mini-retrospective at the Kasmin Gallery that traces her trajectory from the ’60s to the present, Bernstein wore a flaming red coat and struck a characteristic pose, her arms outstretched, as if not only to embrace her audience, but the world at large, whose foibles she continues to fearlessly and gleefully transform into art.

Unlike the rest of her work, much of which features text, the Death Head paintings are wordless, and speak for themselves, both as reflections of the dark days she feels we now live in and as this 82-year-old artist’s own memento mori. They are, as Bernstein herself describes them, impressively “impactful.” And despite their somber subject matter, they burst with exuberant energy, much like the artist herself.

“I started the Death Heads during Covid time,” Bernstein said in an interview in her studio loft in the Chinatown section of Manhattan. “I like the Death Heads because they speak about this time frame. It is the psyche and the zeitgeist of this time frame. It’s about all the things we hear about happening around the world, famine and war. And with Donald Trump, we might actually go to World War III.”

Bernstein made the most of the shock of Donald Trump’s first term, when she was commissioned by the Drawing Center to create a body of work. The resulting 2017 exhibition, “Cabinet of Horrors,” featured drawings, murals and a collection of vintage piggy banks. One reviewer compared Bernstein’s in-your-face artful attack to a “nuclear assault.” She took another sharp shot at Trump in her 2018 Kasmin show, “Money Shot,” a series of eight wall-size black-lit pieces that didn’t stint on biting humor — with repeated images of fanged vagina dentata.

Visitors to her latest show expecting further savage skewering of Trump may be surprised to see just a few paintings from his earlier time in office. “Money Shot, Yellow” (2016) sends up capitalism run amok, and features the Capitol building (spelled Capital) as a slot machine with a vaginal slot and a penile handle. Several swastikas abut dollar signs, and two swastikas bracket Trump’s name. And then there is “Seal of Disbelief,” (2017), the presidential seal with the altered words, “In Evil We Trust.”

Bernstein swears she is now totally finished with Trump. “I worked on my Donald Trump series for a long time, and I have just had it with Donald Trump,” she said.

The retrospective, with archival work facing recent work on the opposite wall, deftly encapsulates Bernstein’s off-again, very much on-again career. Her mixed-media piece, “First National Dick,” (1969), is a sardonic salute to President Richard Nixon. The pièce de résistance, a large charcoal-on-paper triplet of screws, “Three Panel Vertical” (1977), anchors the back wall, and her framed 1995 charcoal-drawn signature is also emblazoned in huge letters on the gallery’s glass front. “I love signing my name,” she said. “In a way it’s a graffiti. And I’ve left my mark: I was here.”

Bernstein was born in Newark, N.J., and raised in a middle-class family — her father taught teaching methods at Fort Monmouth, and her mother worked as a bookkeeper. Her home life was “a lot of screaming and yelling, especially at the dinner table,” the result of an unhappy marriage. “It’s lucky that I got any food down when I was younger. In order to be heard, we had to scream and yell.”

Her need to vociferously express herself is clearly communicated in her work. Its visual messages pull no punches while delivering pungent punchlines, giving her art a strong cross-generational appeal. “My first impression of Judith was seeing her show, which was those wonderful screws,” said the artist Joan Semmel, who has known Bernstein from the late ’70s. “Once seen, never forgotten. They just stay in your mind iconically and conceptually.” She added that “all of the work, from beginning to the end, has been consistent in its strength and clarity.”

Bernstein says of the exhibition: “It’s nice to see the trajectory and also the continuity that I have with the political and the sexual. And how long I’ve been working in that field, and that I’ve not compromised at all. I’ve put out everything that I want to do and I don’t hold back. You should never self-censor.”

Her relentlessly raw humor is a major weapon in her artistic arsenal. “I always had a raucous sense of humor, and I’ve always used a lot of humor that nails what I want to say. And you know laughter, in a certain way, is almost like ejaculation. What connects my work is that my energy level is so impactful.”

While Bernstein’s latest work is equally high-octane, the Death Heads series is something of a departure. Although several earlier pieces included images of skulls, Bernstein has never confronted her own mortality so directly. And yet, despite their looming, even haunting, presence, their execution, with its loopy, liberating lines and neon palette, communicates hope and even joy.

“Let me tell you something,” Bernstein says, “I’m proud of the fact that I’m 82. This is something. I’ve lived a long time, I’ve had a history. And when people say when they come to the gallery they think a much younger person did it, that is not true. I am the embodiment of 82 years, and I mention my age all the time because this is the best time of my life! Because my work is being valued, and I’m being valued, and that’s an extraordinary thing.”