Culture

Assassin’s Creed Shadows Has Lackluster Killers and a Vibrant Japan

Open-world games tend to structure themselves around a central, driving plot. You’ve got to save the planet from catastrophe in Final Fantasy VII Rebirth. In Avowed, you’re seeking the cure for a spreading contagion. The rest of the side-quests — their mini-games and their hidden zones — are mostly extraneous. They’re rest stops along the shoulder of the five-lane highway of plot.

Assassin’s Creed Shadows reverses this formula. Its story line feels diminished and sits in the background of a more vibrant world.

Like past Assassin’s Creed games, Shadows serves up a clear premise: saving Japan from malevolent actors, this time through two controllable characters, Yasuke and Naoe, an African-born samurai and a young shinobi, who are each on tours of vengeance. They’re on the hunt for the Shinbakufu, a group of masked figures set on taking over 16th-century Japan. By the time the credits roll, Yasuke and Naoe will have stabbed, bludgeoned and gutted the lot. But this rote activity of checking bad guys off a list is hardly where the meat of the game is found.

The more remarkable moments to be found in Shadows are in its world, in the gaps between missions, which find you traversing feudal Japan on galloping horseback, driving through its misty gullies and over its forested, windswept peaks. The wilds around you are alive with deer, scampering foxes and rooting tanuki. Elsewhere there are magnificent temples whose realistic depictions are as accurate as you’ll find without airfare, and where your character can solemnly pray before a shrine while the sad twangs of a biwa, a small wooden lute, resound in the background.

It’s a stunningly realized depiction of a country that one would assume gamers are already deeply familiar with. As saturated as the zeitgeist is with ancient Japan, where recent gaming hits like Ghost of Tsushima, Nioh and Sekiro are set, Shadows offers more, digging deeper to deliver a fascinating, grounded picture beyond the wild, natural world. It also captures the many layers of Japan’s feudal society: the bamboo huts of its villages, the quiet shrines and temples, the towering castles and forts of its cities.

It’s when you come face to face with the game’s characters that a deep sense of underwhelm takes over. Wooden performances and murky motivations make navigating the game’s ungainly plot a chore. While the originating premise is clear, assassinating your way to the top rarely delivers any narrative satisfaction. More often than not, your missions require interceding in the conflicts between feuding lords, and it isn’t easy to tell whether the new lord you’re replacing will be much of an improvement over the old one. Nor does the game ever really stop to ask.

It’s a shame, and even a little surprising, how little the game’s plot makes of the potential thematic richness of its setting and its characters. After all, Shadows is set in a Japan begrudgingly opening itself up to foreign influence for the first time. We see warlords who commit massacres in the name of security and peace, and most interesting of all, Yasuke, an African man who was once a slave and has now risen to the rank of samurai. It’s hard not to feel curious about how he finds his way as a stranger in this strange land.

Yet over the bloated length of Shadows, which takes at least 40 hours to complete, very few of these themes are deeply explored. Foreign interference in the country is neatly categorized under the series-canonical boogeyman of the Templar order. The game’s various warlords and daimyos who line up for their slaughter are a confusing mess of nobles and courtiers and their vast extended families; they appear to be your targets only for the tautological reason of being associated with the game’s de facto villains.

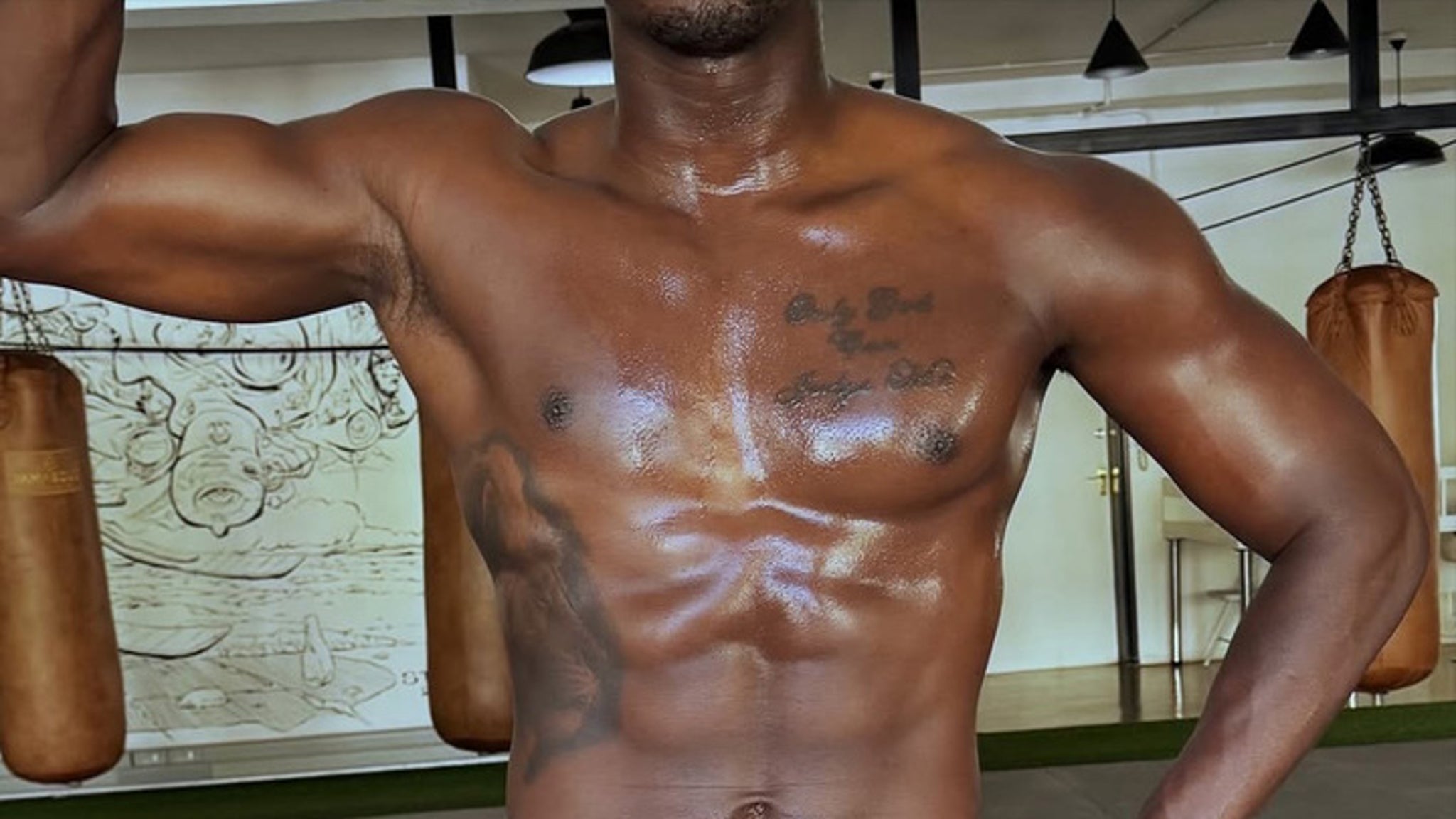

Yasuke himself is a conundrum. Standing head and shoulders above everyone else, he’s the opposite of the stealthy interloper you’d expect an Assassin’s Creed character to be. He stands out like a sore thumb, and that’s the point. Everywhere Yasuke goes, people gasp and step back in shock. When he charges into enemy castles he can knock down soldiers and smash through barred wooden gates. Yet his demeanor is calm, placid, always putting on a smile and looking to defuse situations. He only lets out his anger at select moments later in the game, before sealing it back in.

It’s difficult, as a result, to fully grasp Yasuke’s character, to form an understanding of what he thinks about his surroundings, and how he feels about allies like Naoe. The two maintain a friendly, mechanical camaraderie, acting more like co-workers than intimate friends.

Naoe is far less complex. Driven from her idyllic childhood village by war and violence she follows the classic hero’s journey so closely she might as well have a copy of Joseph Campbell tucked in her ninja’s satchel. There’s even a MacGuffin, a red box holding a secret treasure that she must get her hands on for ambiguous reasons.

In Yasuke and Naoe’s journey to win back this box, ostensibly just a plot device, we glimpse more interesting things. There is a charming espionage-themed mission that demands that Naoe must properly complete a tea ceremony to convince her target of her highborn status. There are missions with poetry readings and ones complicated by star-crossed love affairs. These moments point to the game this could have been, one in which the attention the designers give to human interaction matched the level of care they take with its mountains and forests.

Instead, we have a game without a focus. It’s still an Assassin’s Creed title. We must still spend it stabbing villains with hidden blades, must still go to war against a seemingly infinite well of Templar enemies. It even maintains the series’ layer of goofy science fiction world-building, painting the whole experience as a game within a game, though this aspect is mercifully kept to an easily ignorable sub-menu.

This is all series tradition. But that tradition doesn’t quite work in Shadows. There’s more life in its small moments, like praying at a shrine high in the mountains or romancing the sister of a murdered daimyo, than there is in climbing another tower to assassinate another lord. The plot, with its unorthodox protagonists taking on an evil elite, encourages us to leave tradition behind and embrace a new vision of Japan. It’s a lesson Ubisoft should have taken more to heart when designing the game.

Assassin’s Creed Shadows was reviewed on the PlayStation 5. It is also available on Mac, PC and the Xbox Series X|S.