Culture

‘Grangeville’ Review: Am I My Half Brother’s Keeper?

“I don’t know why we have to do this over the phone,” says Arnold, speaking from Rotterdam to his estranged half brother, Jerry, in Idaho.

That’s how I felt too, at least during the first half of Samuel D. Hunter’s “Grangeville,” a bleak two-hander named for the men’s hometown. Most of what happens happens at a distance of thousands of miles — and feels like it.

The distance might have been mitigated if Arnold (Brian J. Smith) and Jerry (Paul Sparks) weren’t for the most part kept at opposite sides of a dim, featureless stage in Jack Serio’s halting production for Signature Theater. Until late in the play, the set, by the design collective dots, consists only of black walls and a janky trailer door, signifying the characters’ fractured, unsheltered childhoods. The interiorized sound (by Christopher Darbassie) and crepuscular lighting (by Stacey Derosier) lend many scenes the flat affect of a radio play.

But it’s also a problem that Hunter, often brilliant with banality, has buried the characters’ Cain-and-Abel subtext so shallowly beneath repetitive and not entirely credible discussions of their dying mother’s finances. Jerry, an RV salesman and only about 50, cannot figure out how to access her bank accounts online, let alone keep ahead of her bills and reimbursements. Arnold, a decade younger and having fled the family long since, resents being pulled back by end-of-life math. He might as well ask — though it would not be Hunter’s style — “Am I my brother’s bookkeeper?”

Yet an ancient fraternal struggle, like those in plays by Arthur Miller, Sam Shepard and Suzan-Lori Parks — and in the Bible — is what “Grangeville,” which opened on Monday, means to dramatize. Between discussions of prognoses and powers of attorney, we learn in the opening scenes how both men were brutalized by their mother’s violent husbands and her failure to offer protection. (She was often absent on benders.) Predictably enough, Jerry turned into a brutalizer too, in an effort, he now explains feebly, to help the sensitive and proto-gay Arnold survive.

“I was just trying to toughen him up,” he says.

Job well done. Arnold moved about as far as he could from Idaho, developing an impenetrably thick skin regarding his past and trying to put even English behind him. (His husband, Bram, is Dutch.) For years, his buried feelings were most vividly channeled into his artwork: dioramas depicting local Grangeville attractions like the tattoo parlor and the Dairy Queen. Kick-starting his career, these dioramas seemed, to his admirers, to be making fun of America: “the one theme in modern European art,” Arnold says bitterly, “that is consistently evergreen.” But for him they were the one form of home he could tolerate.

In any case, that well has now run dry. Unable to produce new work he likes, Arnold allows his anger to explode as unfocused rancor. “Oh my god,” Bram exclaims, “it’s like shooting clay pigeons with you, I can’t keep track of your grievances!” — as at times I couldn’t keep track of the play’s. If Arnold and Bram are in some stage of estrangement, so, in an overly neat parallel back home, are Jerry and his wife, Stacey.

Nevertheless, it’s in this marital material that “Grangeville” comes alive — largely, I think, because Hunter has contrived to create third and fourth characters from a two-man cast. Almost midway through the play’s 90 minutes, Smith switches without notice from playing angry Arnold to playing reasonable Stacey in a sweet-sad scene with Jerry; their wrangling over child care schedules makes a convincing proxy for the mismatch of their marriage.

And soon thereafter, the mirror image: Sparks switches from playing wheedling Jerry to playing upright Bram in a harrowing scene with Arnold. Bram’s argument that people remain connected to their families whether they like it or not, and that Arnold must therefore go home and make peace, has a similar double meaning for them.

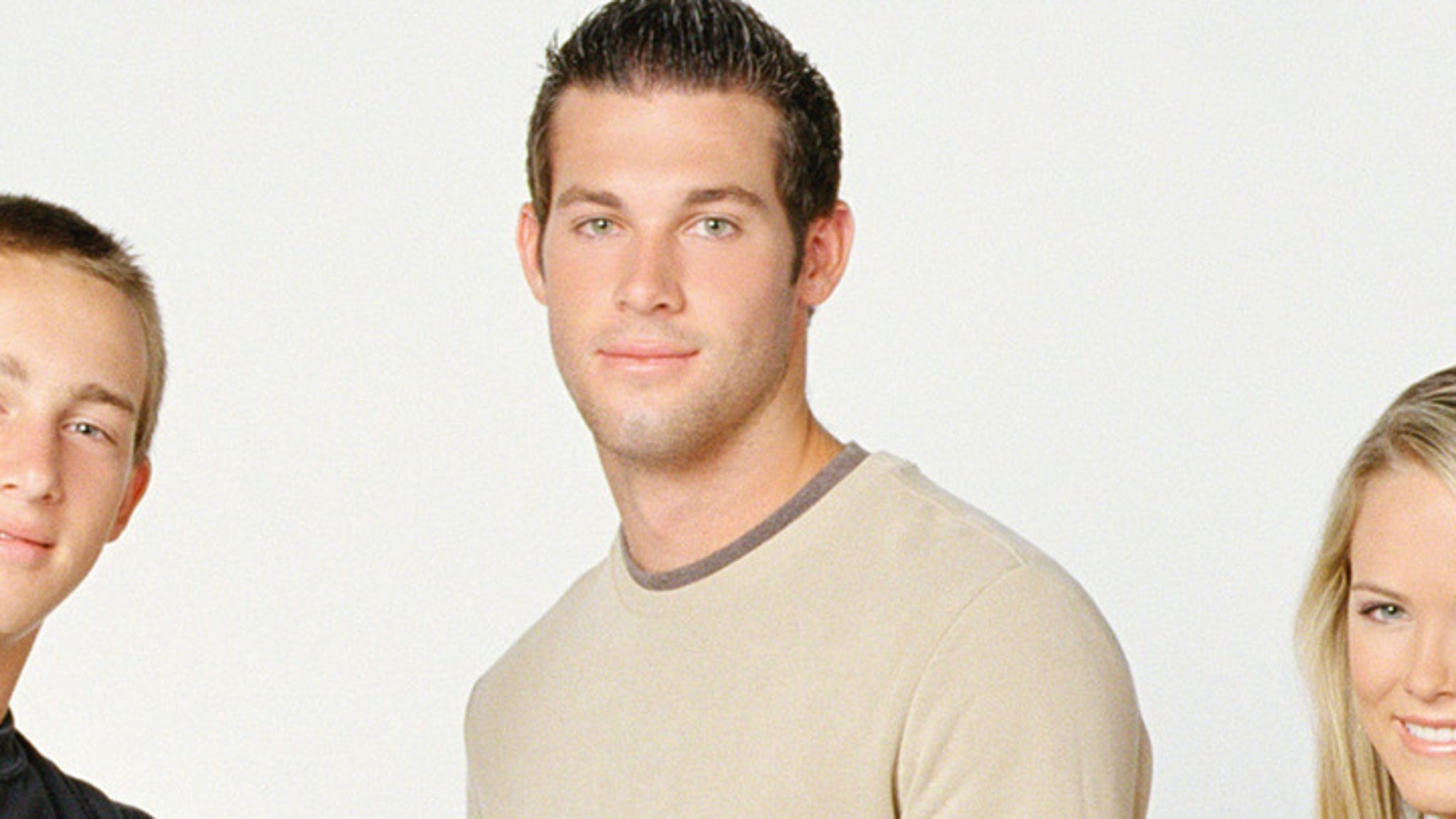

Now that the play’s characters are in the same space, locking eyes as we lock eyes on them, the drama becomes dimensional, and the actors, formerly overplaying, shine. There is something pregnant and poignant about Smith’s portraying a woman, even leaving aside that she is married to his brother. Likewise with the excellent Sparks, a late substitution for Brendan Fraser. His Bram, though intensely logical in his love, brings enough of Jerry with him to suggest the way people keep recreating their family of origin.

The play’s engine having finally turned over, it purrs confidently to the end, which includes a coup de théâtre reminiscent of the one in Hunter’s previous Signature outing, “A Case for the Existence of God.” Like that gorgeous play, too, it offers the idea of incremental hope to those whose lives would not seem to allow it. The trick, as Stacey learns from reading medieval history, is to find the freedom in that. There is no fate, Hunter argues, and his play demonstrates: just an infinity of second chances.

Grangeville

Through March 23 at the Pershing Square Signature Center, Manhattan; signaturetheatre.org. Running time: 1 hour 30 minutes.