Culture

The Most Memorable ‘S.N.L.’ Sketches Where Actors Break Character

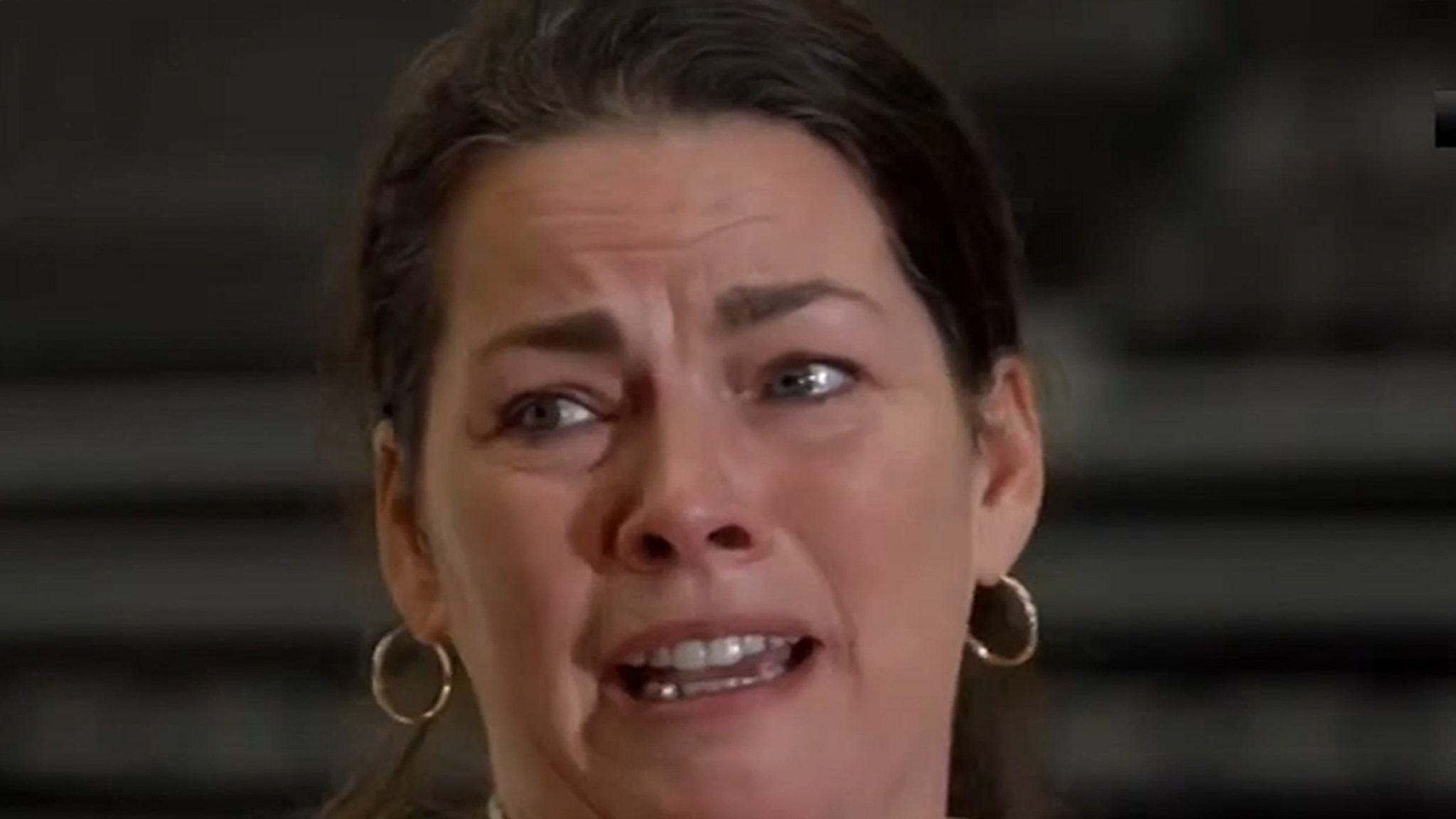

In one of the most popular sketches of the last few seasons of “Saturday Night Live,” Heidi Gardner lost it.

Playing a sober-faced news anchor, she suddenly broke character, convulsing in laughter after seeing her cast mate Mikey Day sitting in the audience of a town hall dressed up to look like Butt-Head from “Beavis and Butt-Head”:

In an interview about this viral moment, she described feeling guilty about it. Lorne Michaels, the longtime producer of the sketch show, has a reputation for hating it when cast members break character.

But over 50 seasons, so many “S.N.L.” performers have done just that (some repeatedly) that it has become one of the show’s signature moves, inadvertent or not — one that usually delights the studio audience and viewers at home. Bill Hader, who often broke, has said, “I think Lorne secretly loved it.”

In general, breaking during a performance, whether it’s a play or a sketch, is considered unprofessional. The argument is that it panders for laughs, destroys the suspension of disbelief and draws attention to the person laughing at the expense of the scene.

“30 Rock” used Tracy Morgan, a former “S.N.L.” cast member, to mock the phony mischievousness of breaking:

The case for it is, well, it works. The audience loved it when Gardner lost her composure. And breaking figures in some of the funniest sketches in the history of the show.

As Debbie Downer on a family vacation at Disney World, Rachel Dratch cracks up early and often, but seeing her recover only speeds up the momentum of this comic gem:

Jimmy Fallon, the cast member most famous for breaking, couldn’t keep it together either:

According to Christian Schneider, who co-hosts “Wasn’t That Special,” a podcast reviewing every season of the show, the first “S.N.L.” break was a muffled chuckle by Chevy Chase in the third episode of the first year:

He made it about two-thirds of the way through a P.S.A. for the “Droolers Anti-Defamation League.”

The most memorable examples of breaking fall into two camps: laughing because a sketch is extremely good or terribly bad.

A notorious disaster happened when Eddie Murphy was dying during a nightclub sketch, and after Joe Piscopo tossed some food at him …

… he dropped his character completely and yelled in an exasperated baritone: “This is live television!” It didn’t save the scene, but he at least made it interesting in a way that only live television can.

One reason people like breaking is it gives them a peek behind the curtain. In this absurd restaurant sketch, Adam Sandler plays an apprentice pepper grinder taught by Dana Carvey. As Chris Farley hams it up as a customer, you hear the more seasoned cast member Carvey do some additional mentoring, quietly telling him not to laugh — but still in character, with an Italian accent:

For die-hard “S.N.L.” fans, these moments add a meta layer of fun. You see the dynamic of the cast as well as that between characters.

In some sketches, the cast appears to be working harder to make each other laugh than the audience. This was often the case with Stefon, the popular club-kid character created by Hader and John Mulaney, a former writer on the show:

Some cast members were known for breaking everyone up. Farley destroyed many deadpans, as in the instantly legendary Matt Foley sketch:

Will Ferrell had a similar reputation. When he played an office worker honoring America after 9/11 with a red, white and blue thong, he was the only one onstage who kept a straight face:

There is sadistic fun in watching Ferrell’s drawn-out line readings undo his co-stars Dratch, Seth Meyers, Amy Poehler and Horatio Sanz. And it only increases when you learn that he set them up by wearing a less revealing outfit in the rehearsal.

Jason Sudeikis brought a similar dynamic to the running Scared Straight scenes. Sudeikis, playing a police chief …

… always tried to break up Hader, Andy Samberg and Bobby Moynihan at the end by hopping on a desk and asking: “You boys learned your lesson?” For regular “S.N.L.” viewers, it gives the sketch some added suspense.

Breaking works if it feels genuine. But it can grate and come off as indulgent when done quickly. Witness Fallon and Sanz in this misguided sketch about leather salesmen:

Fallon also breaks in one of his only lines in the irresistible cowbell sketch, in which Christopher Walken plays a ’70s music producer with a fever, its prescription now known to millions. During his time on “Saturday Night Live,” Fallon cracking up onscreen became an enduring aspect of his cultural reputation.

It’s a more jarring jolt when a normally controlled “S.N.L.” veteran loses it. When the stoic comic virtuoso Phil Hartman broke playing Frankenstein’s monster, it was so rare that it doubled the impact of an already funny sketch:

Similarly, Kristen Wiig cracked up so many of her co-stars over her seven seasons on the show, it felt well-earned (or even karmic) when she couldn’t help giggling at a rubber chicken:

Then there are those who fought the good fight and succeeded. Chris Parnell was the only one who kept his composure in the famous cowbell sketch. And Vanessa Bayer was impressively disciplined on several episodes, including sticking to character beside a breaking Hader in an ill-fated holiday sketch:

The sequence itself was so weak, it never made it to air — it was released online. But it includes my very favorite example of breaking.

The sketch features Hader and Fred Armisen as apartment building doormen during the Christmas season. The humor leans largely on the thin foundation of their thick accents as they make annoying small talk with families, and the performers seem to lose faith in the comedy quickly. Flailing through a long story about Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer, Armisen stares right at the child actor and completely loses it, laughing in his face.

The boy stood there and didn’t budge, a feat of professionalism in the face of this comedian losing it. There’s something about this juxtaposition that, well, can make you break.

Breaking is a failure. That’s also its appeal. After all, human weakness is comedy’s greatest subject.

Michaels knows this. Just check out a 1996 episode when the presidential candidate Bob Dole makes a cameo in a sketch with Norm Macdonald playing him. Michaels shows up, and if you look closely you can see him breaking: