Culture

10-Minute Challenge: A Finished, Unfinished Portrait by Alice Neel

Thanks for spending time with the art! If you want to look a little longer, just scroll back up and press “Continue.” Now, we’ll tell you a little bit about it.

In her six-decade career, Ms. Neel was best known for her portraits across a wide spectrum of humanity — poets, Puerto Ricans, performers, pregnant women, politicians, prominent people and poor ones, queer, straight, Black, white, nude, clothed, famous and ordinary.

Her paintings depicted people who had been through what she called the “rat race” of life. “They’re damaged and they are mutilated, but they are still kicking,” she told Johnny Carson in 1984

Ginny and Elizabeth, 1975

Ms. Neel painted at an easel, her eyes darting from the subject to her oil paints to the canvas, in sessions that could last hours.

“No coffee was served,” her son, Hartley, said. “There was no social aspect to this. She almost never had somebody else watching her paint. And so it was a very intimate experience.”

Here she is in 1969 painting her daughter-in-law, Ginny:

“She was so focused on capturing the personage and soul of the person that she was painting, that it overrode everything,” Hartley (Ginny’s husband) told us. “I think that she was almost in a trance when she painted.”

In interviews over the years, Ms. Neel said she identified with her subjects completely: “I go so out of myself and into them that, after they leave, I sometimes feel horrible. I feel like an untenanted house.”

The writer and critic Hilton Als, who has curated several shows of Ms. Neel’s work, including one currently on view in Los Angeles, felt this connection when he was introduced to Ms. Neel’s work in college.

“I was blown away by a kind of psychic energy that was in the work,” he said. “There was a way in which she was trying unequivocally to understand the way the body was married to the soul and the way the soul was married to the psyche.”

The person in the painting you just spent time with is James Hunter. It was common for Ms. Neel to spot people in public that she wanted to paint and invite them to her studio. Mr. Hunter was one of those people.

It was 1965. The United States was sending more troops to Vietnam, and Mr. Hunter had recently found out he was one of them. He was scheduled to leave for basic training within the week.

During the session in her apartment, Ms. Neel outlined Mr. Hunter’s body, his hands, his legs and the chair on the five-foot-tall canvas.

One hand is filled in. The other is just a sketch.

Mr. Hunter’s ears remain in outline; the light on his nose, his lips, his eyes are more fully rendered.

“Those downcast eyes,” Mr. Als said. “They’re killer.”

“He’s just a beautiful person,” Mr. Als said. “She’s looking at him with complete empathy.”

Mr. Hunter isn’t looking back at us.

The full piece is spare — mostly raw canvas — and yes, unfinished. Mr. Hunter didn’t return for a second session.

Mr. Als views these gestural marks outlining his legs, his jacket, his hand as a kind of memory of Mr. Hunter. “I think she brilliantly conveys living in a kind of stasis and the poignancy of wondering: ‘What will become of me? Will I be a memory? Or will I be a person?’”

We don’t know what happened to Mr. Hunter.

Curators at the Metropolitan Museum of Art did extensive research for two shows that featured this painting, according to Kelly Baum, a curator who worked on both shows. But they could not locate Mr. Hunter or firmly establish his fate, only that he probably did not die in the Vietnam War.

Though clearly unfinished, Ms. Neel considered the painting complete anyway; she signed it and included it in a retrospective of her work at the Whitney Museum in 1974.

“I’m sure she wanted to paint him completely, paint his body and all the rest,” Ms. Neel’s son said. “But at the moment that he was no longer available, that became the image. And she saved it and loved that painting as much as any.”

The painting was kind of a bittersweet breakthrough for Ms. Neel, Ms. Baum said. She lost her subject, but her subsequent work became looser — more, well, unfinished.

“There’s so much room for you to play and project and imagine,” she said. “And I think that’s an interesting contradiction. Like maybe the less the artist gives you in this case, the more generous it is.”

Mr. Als has pored over her paintings, specifically the pictures where sitters are “incredibly bound up with being.”

“We don’t really take a lot of time to consider being alive,” he said. “And Alice was sitting day after day in that apartment in Spanish Harlem and then later on the Upper West Side, day after day, considering how and why we are alive. That’s an amazing feat not only of discipline, but of production. And hope.”

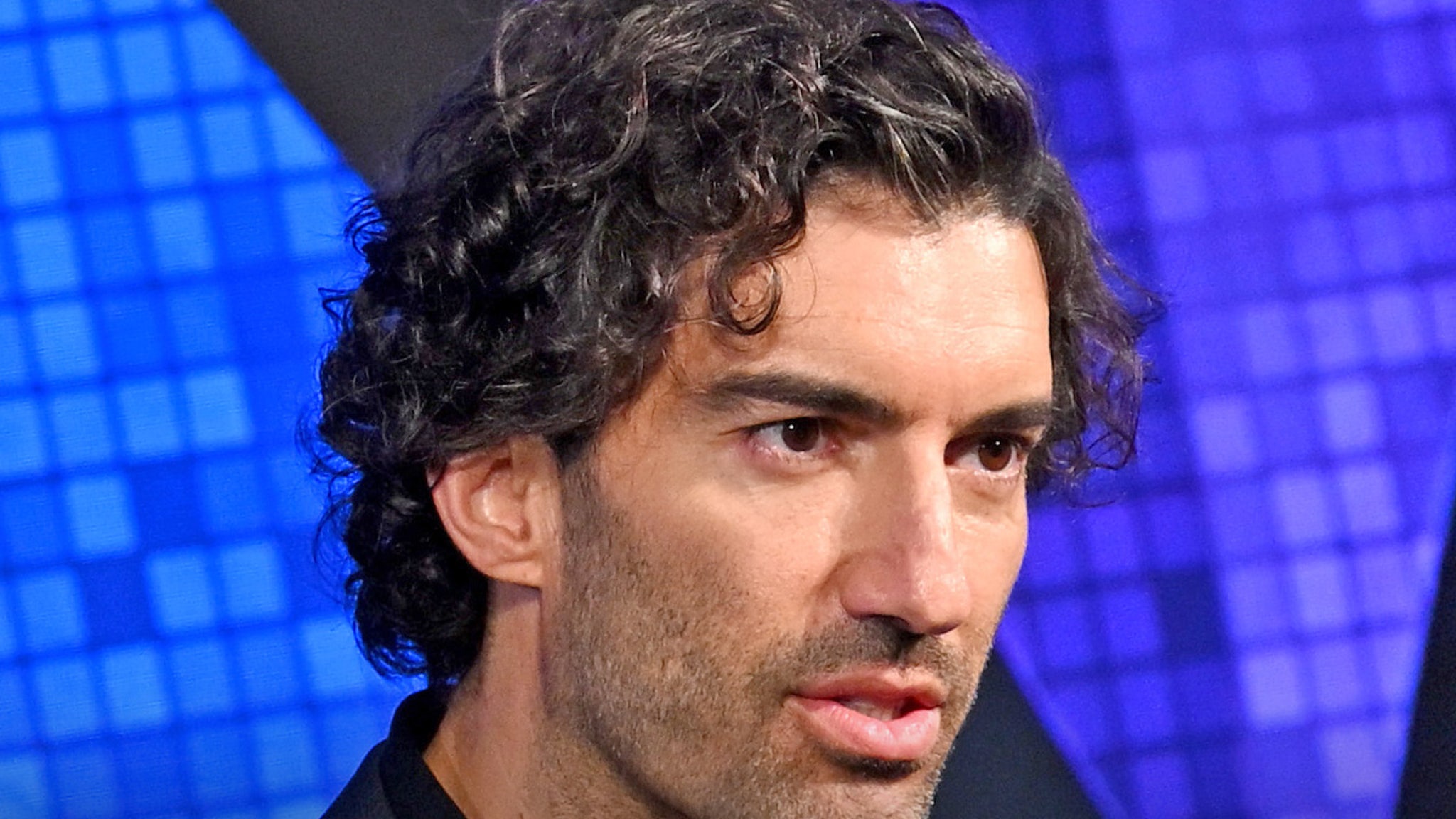

“Black Draftee (James Hunter)” in a 2021 show of Ms. Neel’s work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Sasha Arutyunova for The New York Times

![How Did ‘Yellowstone’ Season 5 End? Breaking Down [Spoiler’s] Death How Did ‘Yellowstone’ Season 5 End? Breaking Down [Spoiler’s] Death](https://www.usmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/How-Did-Yellowstone-Season-5-End.jpg?crop=70px%2C193px%2C1930px%2C1012px&resize=1200%2C630&quality=78&strip=all)